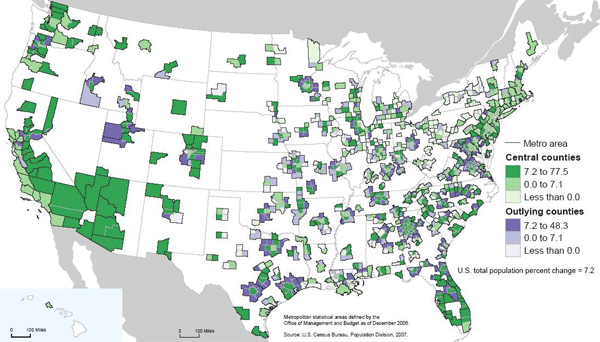

Positive Population Change for Cities and Outlying Areas.

Positive Population Change for Cities and Outlying Areas.Whatever the case, many Americans are continuing to seek their dreams in suburban and exurban areas. With the recent onslaught of coverage on suburban foreclosures it is germane to ask what will the suburban landscape look like in half a century? Will foreclosed houses become productive gardens for remaining residents? That possibility, while alluring, seems unlikely without concerted effort and regulation. It is more realistic to assume that the suburbia of the future will look like the cities of the present. With these thoughts in my head I decide to take a walk.

Washington Avenue is one of the significant streets of Saint Louis. It spans almost eight miles with fits and starts, beginning at the riverfront and ending in the streetcar suburb of University City outside the city limits. It is best known as the main artery of the former Garment District which has been redeveloped as a concentration of lofts and restaurants. Further west Washington Avenue (neé Terrace) is one of the most exclusive gated streets in the city. In between these two poles, and just north of the posh Central West End, Washington holds clues to the future of the suburb.

Like many thoroughly urban areas, Washington was once a suburb itself. Extending beyond the limits of city development across a wide area known as the Grand Prairie the development of the street was made possible by a new type of transportation: the electric streetcar. A number of car lines ran nearby, including the #10 on Delmar, the #15 Hodiamont on a private right of way several blocks north, and another line running on Olive from Lindell to Walton. [For the 1910 Map, click here.] Much of Washington was built as speculative development, and as we walk through the intersection of Walton and Washington we will see a perfect example.

4617-4641 Washington Avenue.

4617-4641 Washington Avenue. These two family flats were built as part of a row of eight in 1901. Their lot division, atypically small even for this area, was the result of being near the junction of Washington with Olive and the streetcar line. At the time these flats were built, land value was a direct function of distance from fixed-route public transportation. It was only with the switch to buses and the uncertainty of a potentially variable route that this relation was severed.

Despite alternating brick and stone units, common features such as the placement of the turret and Jefferson windows above the porch tie the composition together. Two units have been demolished and the windowless one is in the clutches of Bowood Gardens, but despite the removal of integral context the power of the alternating repetition still makes for an excellent streetwall. Compare this image mentally with a typical modern suburban street. If every third house was replaced with an overgrown lot, how would it compare with the above image?

Wash Walt Taylor

Looking at the 1909 Sanborn map of the block it is evident just how much urban fabric the area bounded by Walton, Washington, Taylor and Delmar has lost. All of the red markings denote buildings replaced by vacant lots or parking, the green marks denote buildings replaced by more recent buildings. While I was unable to find any information on it, the loss of the courtyard apartment at Taylor and Washington was tragic. Despite all the losses, the relatively narrow block depths and remaining buildings still manage to keep the block from feeling like a wasteland. With suburban lots typically three to five times wider than these lots, the loss of a single foreclosed house to fire or demolition would have a much more severe impact on surrounding values on the cul-de-sac or road.

I continue walking east on Washington, crossing Taylor and then Newstead. The block of Washington between Newstead and Pendleton has seen some of the most dramatic loss of urban fabric.

Wash Newstead Pendleton

While this block has retained the wide-lot platting that belies its upper class origins, most of the original houses have been demolished. On the south side eight remain standing, on the north side only six. In contrast to the suburban style infill built on the south side in 1997 across two lots, the 2006 infill homes by X3 Developers are striking in their competency.

Three infill houses on Washington by X3 Developments.

Three infill houses on Washington by X3 Developments. Built at 4341-4347 Washington to replace three houses dating to the mid-1890's that had unfortunately been lost, these three infill units notably carry the masonry entirely around the building (unlike some recent failures). While the arched windows on 4345 are kitchy and not architecturally appropriate to Saint Louis, the flanking models have a nicely understated referencing of Richardsonian Romanesque. Since these sold for half a million dollars apiece, I feel compelled to note that the hipped roofs are a let down, the tectonics are too flat without more complicated brickwork and the stoop/stair combination is a blatant and unnecessary reference to brownstones over 1,000 miles away. While I would prefer for infill to refer to surrounding structures but ditch the weak historicism like Anthony Robinson's recent projects I would still not be disappointed if they filled in the rest of the empty lots on this block with more considered variations of these.

The true gem on this block is not the new infill, but an old remnant.

Service Station at Pendleton and Washington.

Service Station at Pendleton and Washington. This service station was built to replace a mansion sometime in the 1920s to serve the growing motoring demand of the wealthy residents in surrounding neighborhoods. The beautiful black Vitrolite facade probably dates from the 1950s. Note the elegant reveals of glass block at the sides of the facade as well as the combination of green window mullion and chrome. The architecture of this facade displays a confidence not found even in the half million dollar infill houses. At the time of the facade installation this service station was a block away from the epicenter of St. Louis nightlife at Gaslight Square. The decline of Gaslight Square meant the decline of business for this little gas station. It served for a time as the home of Kugman Motors, but it has been vacant since at least 1989.

Wash Pendleton Whittier

The block of Washington between Pendleton and Olive has seen much change in the century since the Sanborn Map was complied. The failure of Gaslight Square led to the demolition of the north side of Olive between Newstead and Whittier in the early 1990s. As part of the Gaslight Square redevelopment Pendleton was realigned to connect with Boyle. This ironically eliminated the jog that gave Gaslight Square its name. The two institutions that anchored the block disappeared decades ago. Bishop Robertson Hall was a private Episcopalian school with a 2,000 volume library that closed in 1915. The Episcopalian nuns of the Good Shepard then moved to Baden. The more significant of the two, Hosmer Hall had been established as an elite girls school in 1884. Today it is remembered as the alma mater of poet Sara Teasdale and for infamously banning hair extensions in 1909. A decade after the World's Fair Hosmer Hall moved to Clayton. The school closed and sold their building to Clayton in 1936 and it became known as the Wydown School until it was raised and replaced in 1965 by the present Wydown Middle School.

The final stop on our walk is in front of one of my favorite buildings in Saint Louis. Often I daydream about having unlimited resources to realize any project in the city. While a part of me longs to save and rehabilitate the apartments at 5315 Cabanne, the building at 4005 Delmar, or maybe even the San Luis, only one house calls to me.

4243 Washington.

4243 Washington. 4243 Washington avenue is unique. For every building in Saint Louis exploding with ornate terra cotta or wrought iron ornament there are many buildings that derive their aesthetic power from restrained geometries that presage the modern movement by decades. In that class 4243 Washington stands out with an unprecedented geometric purity that reinforces its three powerful stories.

4243 Washington.

4243 Washington. Built in 1891 on the northern edge of the Central West End 4243 Washington anticipated a density and level of income that was never to coalesce. Unlike the majority of the houses on the block 4243 had three full stories combining for 5,200 square feet on a standard 50'-0"x150'-0" lot. In 1909 it was the only house on the block to have a two story carriage house. It is unclear when the carriage house was demolished, but a garage constructed in 1994 now has taken its place.

By the late 1950's the neighborhood had changed. Upper and upper middle class residents had either retreated into the private streets to the south or left the city entirely. According to a twenty year resident of the block named Lee, during the heyday of Gaslight Square older neighbors recollected Tina Turner stayed with a friend at 4243 when she was avoiding Ike Turner. After the fall of Gaslight Square Lee recollected that there was a lot of crime and prostitution in the area. As buildings burned and were demolished most of the residents left. 4243 survived under the same owner as the neighborhood got quieter and quieter. In November 2003 long-time owner Louise Holland sold 4243 for $125,000. New owners Ralph and Katrina Russell bought the property and began to reahab the house. Unfortunately they lost it in foreclosure in 2007 while in the process of replacing the windows. The empty shell was then sold for $79,000 to a Kevin Settle who sold it to M&J Enterprise for $95,000. The new owners have not paid property taxes since they have purchased the building.

If ever there was a building uniquely suited for a vacant building registry, stabilization, seizure, and resale this is it! However, even boarding second floor windows (let alone tarping roofs!) is "too expensive" despite the far greater economic and environmental costs of demolition. Disregard that: in this city, like in our equally visionary sister city, demolition means jobs.