In recent days, the Saint Louis Post-Dispatch has run a number of stories examining what Saint Louis must to to transition from being a formerly powerful industrial city to a successful 21st century city. Of note are the articles challenging Saint Louisans' reliance on organizational mentality and large corporations and difficulty attracting and retaining talent.

As someone who spends a considerable amount of time considering the future of Saint Louis and its potential sustainability, I feel this will prove to be an extremely productive conversation even if the only produce is a heightened a sense of urgency.

I would like to contribute to this discussion by running an as yet unpublished opinion piece that was originally submitted to St. Louis Tableau in 2009.“The idea of a great city never has occupied a comfortable place in the American imagination”

-- Lewis H. Lapham. “City Lights.” Harper’s Magazine, Issue 285. July, 1992. p. 4.

“If the city were to decline, no one would rebuild it according to the present plan. That alone discloses our own judgement on our cities.”

--Henry Ford as quoted in

“Detroit Vacant Land Survey,” Detroit: City Planning Commission, 24 August, 1990.

American cities have occupied a culturally vulnerable position since the coalescence of our nation. The United States was founded on a doctrine of equality and self-sufficiency. While the urban center had once represented a freedom from feudalism in Europe, American freedom was, from the beginning, predicated on land-ownership and independence of labor. As the French philosopher Henri Lefebvre notes "Urban democracy would imply an equality of places" while the traditional urban ideal of centrality “would produce hierarchy and therefore inequality"

1. Urbanized cities were therefore associated with monarchies and empires. It was Thomas Jefferson’s utopic vision of a nation of gentlemen farmers that precipitated a feud with Alexander Hamilton’s urban Federalists; this philosophical difference led to no less than the birth of American political parties. A century later, the eminent historian Frederick Jackson Turner explained the American psyche using a frontier thesis:

“the existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward, explain American development.”2

While Turner himself thought that the closing of the frontier would result in “the birth of a new nation in America,”

3 Jefferson’s vision still resonates strongly in current debates about suburbanization and in NIMBY resistance to density throughout the country.

The decline of American cities is most commonly attributed to the destructive structural changes of the postwar period. While factors such globalized economic forces are geographically neutral, many other changes were certainly motivated or effected by the anti-urban ethos that has permeated American culture and politics since the beginning of the country. The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 spawned the interstate system, decentralized industry, and led to the demolition of significant tracts of every large city. The National Housing Act of 1937 created the Federal Housing Administration loan program. FHA subsidized mortgages reflected the anti-urban convictions of the period through numerous measures including the disinclination for multifamily building loans, prioritization of single-family home loans, and limitation of rehabilitation loans to short durations with miniscule amounts.

The net result of these policies was the subsidization of a climate where it was easier and cheaper for a family to buy a new home in the suburbs than to renovate an existing one in the city. With a clear prioritization away from the city, the population shares of cities within metropolitan areas decreased from roughly seventy to forty percent. Cities such as St. Louis lost over sixty percent. The result of this migration was a declining commercial base combined with a service intensive and poorer population. This caused cities to become more reliant on public revenue. With less power, cities assumed a lower profile in American culture and “Americans [were] thereby inclined to be more accepting of the many disruptions and disparities that engulf them and to acquiesce more readily to society’s dominant interests.”

4  The transfer of wealth from the cities left them unable to address escalating problems. Photo by author

The transfer of wealth from the cities left them unable to address escalating problems. Photo by author.

The cultural neglect of cities in combination with an increased population of disadvantaged residents led decreased accountability. Self-interested bureaucracies either grew ineffectual or, failing at traditional redevelopment strategies, desperately grasped for larger and less advantageous forms of development. Most cities entirely neglected small businesses and committed to an increasingly cutthroat gamble to attract and subsidize large corporations. This reactive strategy had its root in anti-urban attitudes and was predicated on an understanding of development as an adversarial game of zero sums.

St. Louis Marketplace, built with generous Tax Increment Financing, is now failing due to metropolitan retail competition. Photo by author

St. Louis Marketplace, built with generous Tax Increment Financing, is now failing due to metropolitan retail competition. Photo by author.

As Kingsley Davis wrote in 1965:

“In the later stages of the cycle ... urbanization in the industrial countries tends to cease. Hence the connection between economic development and the growth of cities also ceases”5.

The economic gains of the city had to be won from outlying suburbs or other regions, and all political effort should be expended towards these ends rather than fostering growth at a larger scale. These stopgap strategies resulted in an urban core characterized by vast swaths of neglected and deteriorating neighborhoods and punctuated by autonomous complexes and speculative developments.

Resources are withdrawn from deteriorating sections of the city to enable high profile development projects. Photo by author

Resources are withdrawn from deteriorating sections of the city to enable high profile development projects. Photo by author.

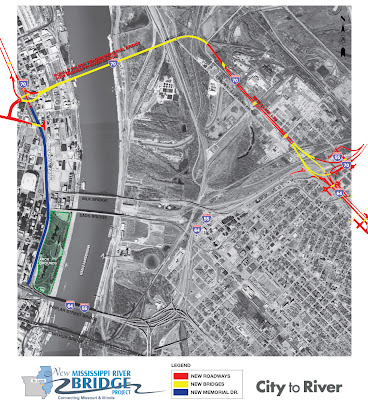

It is this form of urban redevelopment that U.S. News & World Report reporter William Allman assessed on his homecoming to St. Louis:

“Coming back to St. Louis after many years ... the city’s surface has changed considerably... [T]hese changes, while putting a shine on the old city, are merely cosmetic. The downtown areas seemed designed primarily for tourists”6.

That cities have suffered extensively in the past decades as a result of cultural bias and legislative subsidization is well established, but where do we go from here? Allman’s assessment still rings true in St. Louis today. One smirking critic derisively assessed improvement efforts surrounding the 2009 All Star Game as “lipstick on a pig”

7. Clearly current paradigms are not wholly succeeding, nor are they taking advantage of several assets possessed by St. Louis and many other shrinking cities.

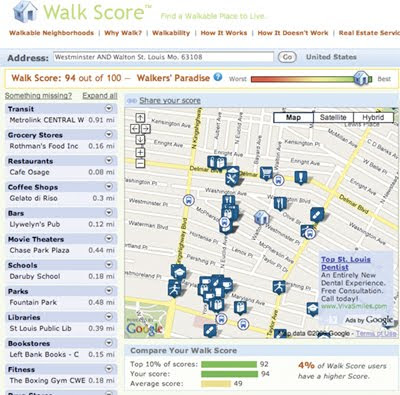

First, the low property values throughout the city and the fine grain of existing development and platting are an asset, not a liability. Low property values mean a substantially more affordable cost of life and greatly increase the potential to cement ties to a community through property ownership. For a small businessperson, cheap rents can mean the difference between failing or expanding to buy the premises. Furthermore, the small scale of neighborhoods and buildings makes renovation and maintenance substantially more manageable and enables more residents to acquire property for rehabilitation and lease. It is counterintuitive given the fragmented nature of urban landholding to continue pursuing large-scale suburban development strategy in urban areas. To do so is to ignore the powerful economic potential for upward mobility and increased tax bases through grass-roots redevelopment. St. Louis’s ravaged but remarkable building stock represents the single greatest asset of the city, and its affordability represents an extraordinary potential to attract the businesspersons and innovators who will shape the next century.

The cycle of economic stagnation described by Kingsley Davis is based on one major variable. His analysis on the decline of urban growth was premised on the cessation of people moving from agrarian areas to the city, for “once urbanization ceases, city growth becomes a function of general population growth”

8. Therefore, another potential for city growth in an urbanized society is not based on poaching jobs from other municipalities, but on attracting new immigrants to the nation and to the city. By enabling them to start businesses and facilitating their upward mobility the tax base may rebound from the damage caused by suburban flight. A recent Brookings institute paper studies economic success and the patterns of movement and resettlement in the metropolitan area. The authors note that such upward mobility “may be the most important force operating in metropolitan areas, but urban public policy has taken little account of it”

9. St. Louis needs to attract immigrant and young entrepreneurs by making a serious commitment to market its affordability.

The city must connect potential entrepreneurs with real estate opportunity. Photo by author

The city must connect potential entrepreneurs with real estate opportunity. Photo by author.

Many strategies to attract immigrants and small businesspeople require far less investment than current initiatives. First, an accessible and comprehensive database of vacant and available commercial and retail spaces is urgently needed. If this were coupled with a broad-based homesteading program that would dispose of the approximately 9,300 parcels of land owned by the city Land Reutilization Authority,

10 these programs could do more to revitalize the city than any corporate redevelopment. For an example of such a program we need only look down the Mississippi to the small city of Paducah Kentucky. Paducah’s Artist Relocation Program

11 combines real estate services with rehabilitation assistance to attract live-work artisanal small businesses to a designated neighborhood. Once entrepreneurs can be attracted to set up businesses, the city must continue assisting them by simplifying permit processes and providing tax incentives to use local suppliers and employees. Finally, the building stock of the city must preserve a range of scales and price points to allow for upward mobility and aging without forcing relocation.

The city can capitalize on its greatest asset, its historic building stock, through a concerted effort to encourage entrepreneurship and immigration.. Photo by author

The city can capitalize on its greatest asset, its historic building stock, through a concerted effort to encourage entrepreneurship and immigration.. Photo by author.

The city of St. Louis has a difficult habit of comparing itself with Chicago, but let us examine New York for a change. In a recent article,

New Geography reports that a culture of favoritism towards major development interests has led to an increasingly fraught climate for small businesses in America’s most urban city. In a survey of Hispanic business owners “84% believe New York City is no longer a good place for immigrants to open their businesses”

12 yet when asked where they would recommend opening a small business the majority still recommended the Northeast.

With an unbiased reappraisal of our assets and a new policy that takes advantage of our low costs, publicizes our opportunities, favors small business creation, and assists upward mobility St. Louis could take over where New York has failed. What are we waiting for?

1 Lefebvre, Henri. The Urban Revolution. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2003. p, 124 .

2 Turner, Frederick Jackson. The Frontier in American History. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1921. p. 1. Available online here.

3 Turner, The Frontier in American History p. 311.

4 Beauregard, Robert A. Voices of Decline. New York: Routledge, 2003. p. 245.

5 Kingsley Davis “The Urbanization of the Human Population,” in the City Reader, ed. Richard T. LeGates and Frederic Stout (London: Routledge, 2003) p. 30.

6 Allman, William F. “St. Louis” U.S. News & World Report, vol. 107. December 18, 1989: p.49-50. As quoted in Beauregard, Robert A. Voices of Decline. p. 222.

7 Hamilton, Keegan. “Extreme Makeover: All-Star Edition: St. Louis is cleaning house for the midsummer classic, but is it, well, lipstick on a pig?” Riverfront Times. July 7, 2009.

8 Davis, “The Urbanization of the Human Population” p. 30.

9 Bier, Thomas. "Moving Up, Filtering Down: Metropolitan Housing Dynamics and Public Policy." Available online here. September 2001.

10 Montee, Susan, et al. "Audit of the City of St. Louis Community and Economic Development Offices." Available online here. April 2009.

11 For more on the Paducah Artist Relocation Program see http://www.paducaharts.com/

12 Null, Steve. "New York City Closes Shop." Available online here. August 7 2009.